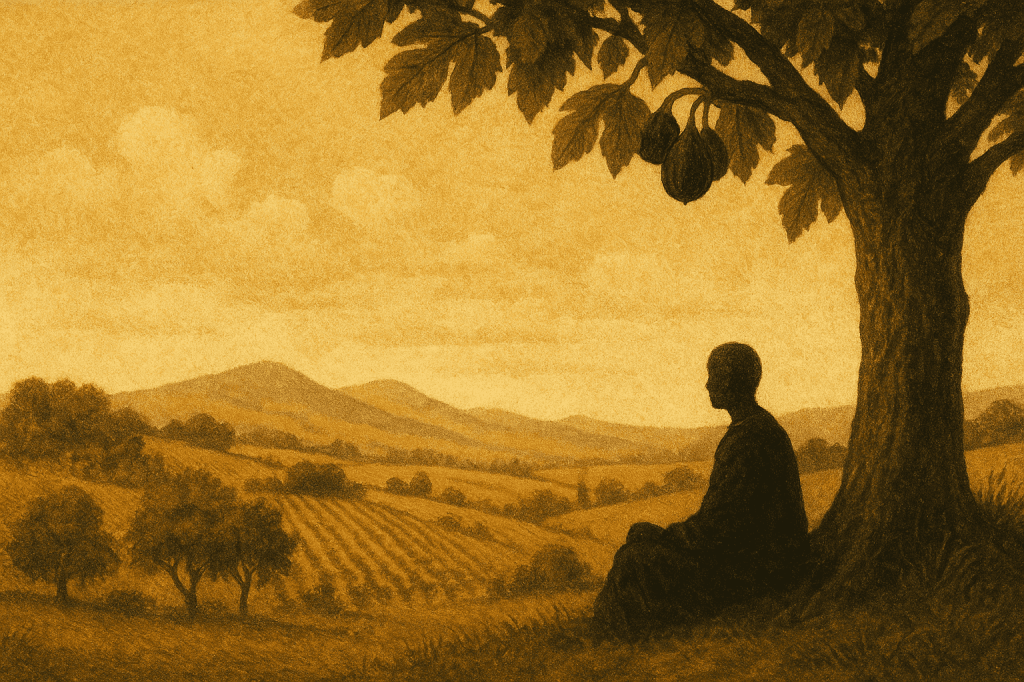

Inspired by Micah 4:4–5

There are certain passages of scripture that seem to arrive not just for the moment in which they were written, but for every moment where the soul of humanity feels disoriented, weary, or divided. Micah 4:4–5 is one such passage. It speaks softly, but with enduring clarity.

“Everyone will sit under their own vine and under their own fig tree,

and no one will make them afraid,

for the Lord Almighty has spoken.

All the nations may walk in the name of their gods,

but we will walk in the name of the Lord our God

for ever and ever.”

Here is a vision of peace that doesn’t depend on sameness. A world where each person is at rest, without fear or threat, under the shelter of their own vine. A world where the spiritual lives of others are not seen as dangers to be corrected, but as journeys to be respected—even while walking a distinct and devoted path oneself.

This is a deeper kind of peace than the world often imagines. It is not about everyone agreeing, nor is it about retreating into private spirituality and leaving others behind. It is about the kind of inner anchoring that makes space for others. Micah’s prophecy is not merely political or poetic—it is profoundly spiritual. It gestures toward the posture of someone who has found peace with God and no longer needs to police the spiritual journeys of others.

It is tempting to think that the purpose of Christianity is correctness, or moral achievement, or religious belonging. But from the earliest voices of the Christian tradition, a different truth shines through: the ultimate aim of Christianity is union with God. This is not just about believing certain things, but about becoming something new—being drawn into the life of God, through Christ, in love.

The early church fathers and mystics alike spoke of this union with reverent awe. Athanasius famously wrote, “God became man so that man might become God”—not to suggest we become gods, but to describe the intimacy and indwelling that Christ offers. Through Him, humanity is not simply instructed, but transformed. In Christ, God makes union possible—not only in the life to come, but in this life now. That is the beating heart of Christian spirituality: not control, but communion.

And so Micah’s vision—of each person sitting under their own fig tree—sits comfortably beside this truth. It is not a contradiction of the gospel, but a mirror held up to its deeper intention. For true union with God cannot be achieved through fear, coercion, or conformity. It must be chosen, welcomed, received. And that means allowing space, in oneself and in others, for the journey to unfold.

What this looks like today is deeply relevant. Many are seeking spirituality without rigid frameworks. Others are quietly returning to the sacred, but in ways that don’t look like traditional religious participation. For those grounded in Christ, this is not a threat. It is an invitation to live their faith more fully—not by forcing belief, but by embodying love.

Walking in the name of the Lord, as Micah describes, becomes a daily rhythm. It is a path chosen not out of superiority, but out of sincerity. It is walking in the way of Jesus—who didn’t cling to power but knelt to wash feet, who didn’t enforce religion but opened hearts. To walk in His name is to walk humbly, yet faithfully. It is to live in alignment with grace.

This alignment—between belief, action, and inner truth—is what gives faith its quiet power. It moves a person from performance into presence. There’s no longer a need to convince others when one is living from the centre. The fig tree becomes a symbol of that rootedness—a life that bears fruit, offers shade, and stands as it is, unafraid.

The Celtic Christian tradition carries a resonance with this kind of living faith. It sees God not only in church walls but in rivers, winds, and open skies. It remembers that the world is saturated with the presence of the Divine, and that Jesus is not only the doorway to union but the very rhythm of life itself. In this tradition, walking with God is not about retreating into correctness but stepping fully into life—awake, attentive, and aligned with the Spirit.

Micah’s vision also points to the communal implications of this way of being. “No one will make them afraid.” There’s something profoundly ethical about spiritual maturity. When people are rooted in love, they don’t need to dominate. When people are at peace with God, they can live at peace with others. This isn’t passivity. It’s a courageous refusal to live by fear. It’s the decision to allow others to find their fig tree while tending one’s own.

To walk in the name of the Lord our God forever is not to walk in isolation. It is to walk deeply, steadily, into the mystery of God, trusting that the Source of all life will draw all things to Himself in time. It is to trust that grace is bigger than systems and that the vine we sit under is nourished by a love that runs deeper than we know.

This kind of faith doesn’t shrink in the face of difference. It doesn’t feel the need to explain everything. It simply becomes a life lived in the open—where others can see the fruit and decide for themselves whether they, too, want to walk this way.

In an age where faith is often politicised, institutionalised, or abandoned, this simple prophetic image remains: a vine, a fig tree, a human being unafraid. And beside it, the steady walk of someone who knows the path they’ve chosen and walks it with grace.

This is not about avoiding truth. It is about embodying it. The truth that God is love. The truth that Christ is the way, not just to better beliefs, but to life itself. The truth that union with God is not a doctrine to debate, but a relationship to live—slowly, quietly, and with courage.

And from there, everything else begins to grow.

Leave a comment