A reflection on what it really means to follow a King who rides a donkey

Palm Sunday marks the beginning of Holy Week—the final stretch in the story of Jesus’ earthly life. At first glance, it looks like a celebration. Crowds gather. Palms wave. Shouts of “Hosanna!” rise in the air. It’s a moment we often call “The Triumphal Entry.”

But for those willing to look a little deeper, Palm Sunday is anything but straightforward. It’s not the arrival of a conquering hero in the way many expected. It’s not the kind of glory that fits easily into our usual ideas of victory. Instead, it offers us something far more subversive: a picture of true spiritual authority wrapped in gentleness, vulnerability, and trust.

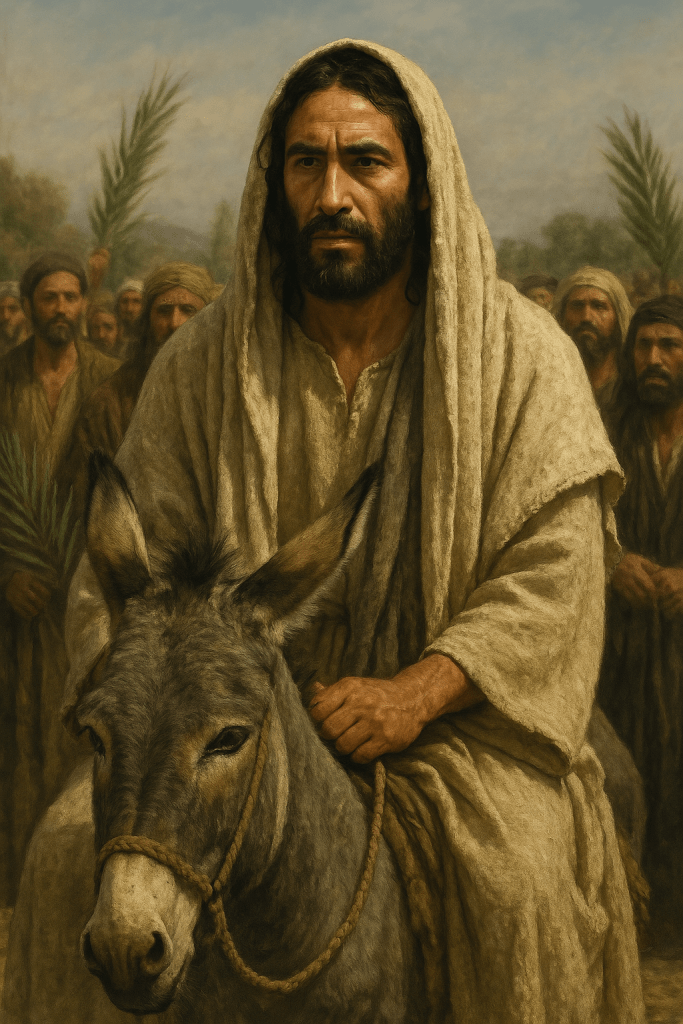

Jesus enters Jerusalem not on a war horse, but on a donkey. Not with soldiers behind him, but with ordinary people—children, women, tax collectors, ex-lepers—waving branches and laying down cloaks. It is a peace procession in a city bracing for conflict. And it begs us to ask: What kind of king is this?

Palm Sunday confronts our assumptions about strength

In many religious and secular circles alike, we’re conditioned to think of power in terms of boldness, visibility, and control. We admire those who rise fast, speak loud, lead with confidence. Even in spiritual circles, we may unconsciously equate holiness with hustle—thinking that if we just pray more, strive harder, prove ourselves worthier, we’ll be acceptable in God’s eyes.

But Palm Sunday stops us in our tracks. Jesus isn’t charging into the city. He’s moving slowly, deliberately, riding a humble animal of peace. There’s no weapon in sight. This is the kind of power that doesn’t need to shout. It doesn’t need to dominate. It doesn’t need to win in the way the world understands winning.

And that’s uncomfortable—because it exposes how much we still want a saviour who will take charge, fix things, protect us from pain, and defeat the people or circumstances that cause us trouble.

But that’s not how this story goes.

Celtic Christianity helps us read this moment differently

The Celtic tradition speaks often of Christ as both king and companion—a high, transcendent presence who is also intimately close. In this view, Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem isn’t just a historical moment, it’s a pattern for spiritual life. It’s about moving toward what is sacred not with force, but with surrender. Not with speed, but with rhythm. Not by dominating, but by returning.

Where Roman ideas of kingship depended on empire and control, the Celtic imagination saw kingship as stewardship—to walk the land with care, to carry the wellbeing of others gently, to serve rather than rule. Jesus embodies this way. He walks it into Jerusalem, not to take over, but to lay himself down.

That kind of leadership doesn’t always look effective from the outside. But it is transformational from the inside.

Palm Sunday invites us to follow—but not blindly

Many in the crowd waving palms were hoping for a political uprising. They saw in Jesus the potential to overthrow Rome. They were celebrating a victory that hadn’t happened yet—but that they wanted to happen, on their terms.

That makes this moment deeply human.

We’ve all hoped for God to show up in a certain way—bold, impressive, definitive. We’ve all looked at the chaos of our lives or the state of the world and longed for a divine fix. Something instant. Something unmissable.

But the Jesus of Palm Sunday isn’t interested in spectacle. He’s not here to fulfil our wishful projections. He’s here to embody a deeper truth: transformation doesn’t come through conquest—it comes through surrender.

He doesn’t come to fix things the way we’d prefer.

He comes to become the way through the very things we fear.

The story isn’t just about Jesus entering Jerusalem. It’s about him entering us.

Palm Sunday is not a passive commemoration. It’s an invitation into a kind of inner procession. A chance to ask: What am I expecting Jesus to be? And what if he’s coming as something else entirely?

It’s also an invitation to examine what we’re carrying into Holy Week. Are we holding demands, hoping God will meet them? Are we approaching the sacred with agendas? Or are we willing to lay them down?

It’s interesting that the people laid down cloaks—symbols of identity, status, and protection. The palms they waved were symbols of victory, yes, but also of hope and longing. Perhaps we, too, are invited to lay down what we cling to, and welcome Christ as he is, not as we wish him to be.

The rhythm of this week is not a sprint to Easter

Palm Sunday reminds us that this journey takes time. Jesus moves slowly, knowing what lies ahead. There’s no rush. And that, too, is part of the lesson.

The tendency to jump from Palm Sunday to Easter skips the transformation. It bypasses the garden of sorrow, the betrayal, the silence of Saturday. But the spiritual path doesn’t bypass. It moves through. Gently. Honestly. Willingly.

In Celtic Christianity, this movement through the valley, the descent into depth, is not a detour—it’s the very place where divine presence is most acutely known. In the darkness. In the not-knowing. In the letting go.

So we’re invited to walk this week with attention—not trying to fix or force, but to remain open to what arises.

A personal reflection for the week ahead

Palm Sunday has always stirred something deep in me. It reminds me that spiritual life isn’t about performance—it’s about presence. It’s not about shouting louder. It’s about listening more closely. It’s not about demanding miracles. It’s about allowing mystery.

So as I enter this Holy Week, I’m asking myself:

- Where am I expecting God to meet my expectations instead of transform them?

- What might I lay down—physically or symbolically—as a gesture of welcome?

- How can I walk this week slowly, intentionally, without rushing toward Easter?

If anything, Palm Sunday reminds us that the deepest spiritual acts aren’t always the loud ones. Sometimes, they look like moving gently toward pain with faith, laying down our assumptions, or welcoming peace when the world expects battle.

Final thought

The King we follow does not force his way in.

He rides a donkey.

He comes in peace.

He enters gently.

And the question he poses, simply by showing up like this, is not, Will you cheer for me?

It is:

Will you walk with me—even when the way isn’t what you expected?

That’s the invitation of Palm Sunday.

And that’s where transformation truly begins.

Leave a comment